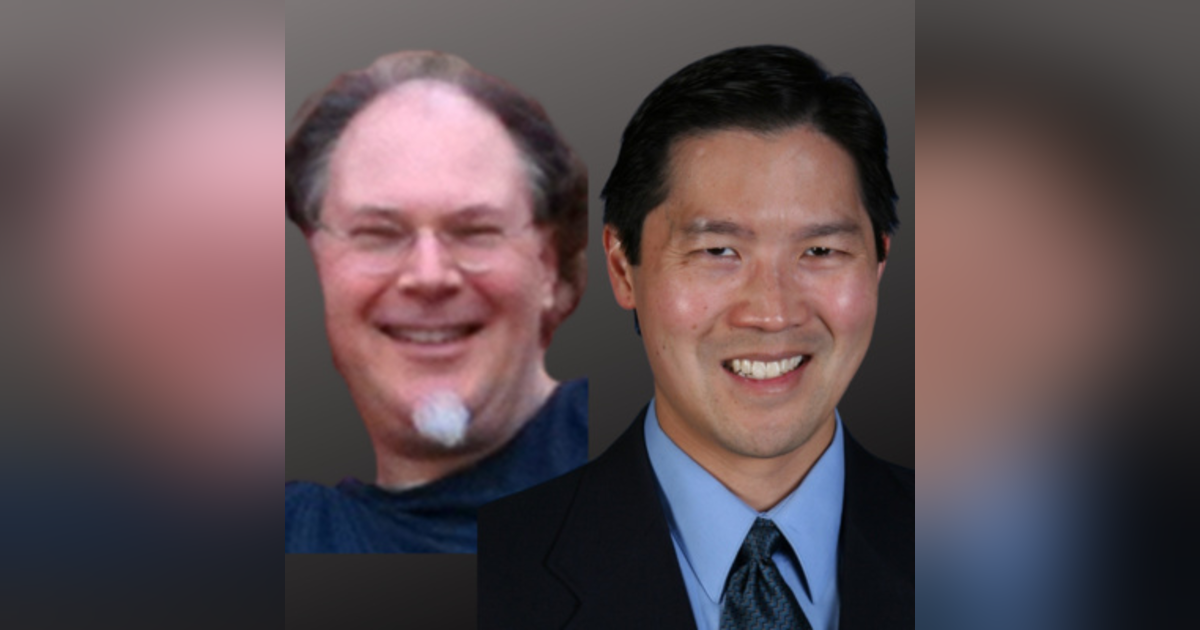

Artifical Intelligence In Pharmacy | Erick Von Schweber and Ed Jai, PharmD

Erick Von Schweber, the CEO of Surveyor Health Corporation,in conjunction with Dr. Ed Jai of Inland Empire Health Plan, share insight about medication management, artificial intelligence, and deprescribing.

https://www.surveyorhealth.com

https://www.iehp.org

Speech to text:

Mike Koelzer, Host: [00:00:00] Eric and ed, for those who haven't come across you online, introduce yourself and tell our listeners what we're talking about today.

Ed Jai, PharmD: My name is Edward Jai I'm the senior director and chief pharmacist at inland empire health plan. Today, we have an opportunity to talk about, uh, some exciting, uh, research results that, uh, we were involved in with surveyor health and

Erick Von Schweber: Eric I'm Eric Von Schweber I'm the executive co-chair of surveyor health as well as acting CEO and CTO. And what we're focused on is bringing new concepts in artificial intelligence to improve care, reduce cost, reduce healthcare utilization, to literally optimize it in ways that it's not been done before.

Mike Koelzer, Host: When you say not done before, yes.

I saw on your website about the military. So we get sick of talking about pharmacy on this podcast. We gotta talk about cool stuff like the military. How does your program tie into it? The

Erick Von Schweber: military. Uh, not directly but indirectly. So we got our start. Our main careers have been in advanced concepts for companies, Locke, like Lockheed Martin Raytheon, et cetera, doing programs for the intelligence agencies, uh, the army, the air force intelligence, of course, DARPA, the CIA, et cetera.

Uh, the agencies were not allowed to name generally. Um, but we've always been in it in a computational aspect to do things like how do you integrate information when you can't have humans do it? How can you do that automatically? Especially if it's intelligence or sad, sensitive, or classified information that not everyone, not all your engineers are allowed to even know.

So that's been one aspect of it. The other aspect is once you've got that information sanitized and integrated and enhanced, how do you apply it and make use of it? How do you make decisions based on it? Um, and so those are the two worlds that we've brought together from our intelligence and military work, uh, working on DARPA programs here to healthcare.

What is DARPA? Uh, yes, DARPA. So the true expansion is the defense advanced research projects agency, but I've also seen, uh, t-shirts that say defense advanced research PowerPoint agency, because we do a lot of, uh, PowerPoint slides with four point fonts. Very, very dense. What did you do with

Mike Koelzer, Host: that?

Don't give anything away, but what does that mean? What did you do with the military?

Erick Von Schweber: So one part of it, remember, we're not operational, we're research and development, so I'm not there in the, uh, in the battle theater. I gotcha. Applying the technology. So one of the factors was, let's say, you've got, and I said, I'm not giving anything away.

This is all public knowledge. Okay. When you look at the modern battle theater, it is very electronic and information dense, but traditionally the pipes, the network pipes, the wireless ones between the various players, between spy satellites, satellite, uh, uh, YouTubes, uh, infantry ships, et cetera. They're all communicating wirelessly over very narrow pipes.

Not like we have, you know, 4k over huge Verizon bandwidth. Okay. It's all conservative on purpose to save resources. It's what you can afford and deploy quickly and achieve very much. Um, hard, difficult, challenging circumstances. And so what you'd like to do is when you have all of these network dependent applications and devices, they need the network.

And if the network Browns out where blacks out, that's not good. Gotcha. You could lose situational awareness of what's happening for minutes and you don't have that time. And so there would be literally planes that are like flying wireless routers, connecting everyone. But if they have to make an unscheduled movement to avoid artillery or to, so they're not noticed now the networks can brown out.

And so we were using our methods and software to look over the network. And in real time balance out the use of the network and to optimize its configuration, to get everyone connected.

Mike Koelzer, Host: So then you take that information, which has a lot of moving parts and we bring it to the pharmacy, which also has a lot of moving parts.

Maybe not when you're talking one drug to one drug, but when you have this polypharmacy with people on 30 or 40 medicines, you can see where there's some parallels to keeping the country alive, to keeping a person alive. So if I understand it, that's where your then entry into [00:05:00] pharmacy comes with a lot of that polypharmacy and all the possible interactions.

And I imagine not just negative interactions, but positive thoughts of what could be done with somebody.

Erick Von Schweber: Yes to bring the two together. Uh, what happened is Linda's mom. Uh, we had, we had no knowledge of this, but, uh, Linda's sister called us up, who was the family caregiver. Co-located in Atlanta with her mom.

We get a call and she says, uh, SIS, I I'm, I, I should have called you six weeks ago. Mom's having this roving, abdominal. Pain, uh, the health system has tested her for everything they could think of. They can't figure it out. Um, I just pulled her out of that system. I got her a new doctor and fortunately, uh, the doctor said it's a medication issue because no one had asked her what meds she was on.

And were there any recent med changes? And there had been. And so for minor arthritic knee pain, this was a woman. If you put a blood pressure cuff on her, it inflated, she said, you're killing me. It's like an eight or a nine . Uh, so for minor arthritic knee pain, they had her on three different opioids, including a full strength, fentanyl pain patch.

Wow. Normally indicated right. For late stage cancer patients. Yeah, for sure. And so the combination, there were no interactions. It wasn't a duplication, but the toxicities were combining in a fashion that were reducing the, I think it's called motility in her large colon. and, uh, we got her weaned off of that, but then Linda turned to me and said, Hey, we've been optimizing military networks.

Could we optimize a drug at regimen rather than a network configuration protocol stack? Hmm. And so I went off, did a quick rapid prototype. She went off and did market research. We came back together and that's when we learned that contrary to what I thought. It's not just her mom that has these problems.

And we saw that the technology, the engine we already had worked and was applicable. And so we decided instead of to, uh, trying to get information, to protect the safety and security of our country, which is where we were doing. Uh, we would work on healthcare and try to help humans. Directly.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Well, you know, I, I like what you just said, Eric, you know, when, when you guys were talking, I was thinking, well, that's a marriage made in heaven because, you know, while Eric and, and, uh, Linda got to geek out a little bit, uh, in DARPA, uh, and, and by the way, uh, I was in the Navy for eight years too.

So we had some terminology that we utilized in the military, like situational awareness. And I think that's one of the biggest issues with regards to too much information or information that got correlated together is how do you make that happen. Information actionable at the right time. And of course, in the right situation.

And when Eric was just showing or sharing about, uh, that one case there, you know, that that could be repeated a million times. Right. And how does an organization with limited resources, uh, which could be a health plan like ours, I H P really understand, uh, what are the priorities to avoid a situation just like that, where the additive side effects of medication are gonna result in patient events, negative events.

Um, and, and so I think it's kind of a. Partnership there where you can take that artificial intelligence approach and then filter out and distill information. Both that is not necessary to, to prioritize or doesn't trigger something, but then take those triggers. Those real concerns, that additive side effects that a drug regimen might expose a patient to.

And then really say, oh, we need to go and, and address this right now. We need to alter the drug regimen. We gotta take something off or modify a dose or put something in its place, another drug. So, that patient, in our case, a member of our health plan would have an optimal outcome.

Mike Koelzer, Host: I would imagine with the information, Eric, that you're able to pull out of that system, that.

A poor pharmacist, calling a doctor in town and saying, look, we're not talking about an interaction here, but I wanna talk to you for three hours about all the possibilities that's happening on this stuff, because I've got this cool program that will show me all this and this guy, or gal's gonna hang up on me.

So, I imagine that something like this is probably built for a health plan where you're all on the same page of lowering costs and doing this or that, because it's probably a boatload of [00:10:00] information that you could pull out of this. To use.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Oh, oh yeah. We have over 1.4 million members and to, uh, understand which members are gonna have, which side effects that are additive or drug interactions and other things that we need to deal with right away is, is almost like pulling a needle out of a haystack.

Right? You just, you, you have too much information. You have, uh, patient members that have 10 meds or they might have 60 medications on board. And so I think the unique thing about what we did and what surveyor health provided was a platform, a technology, a decision support. A tool that can just bring that information to the front.

Like I said, actionable information and, and we have, we have to do things with our members, right. That is both regulatory, but also just really doing the right thing. We gotta look at their drugs. We have to go and make sure that we're doing well by the members. And, it's just really hard for a pharmacist, a clinician to really sift through that information in the time that we have for the 1.4 million members that we have.

And we, you know, we don't have one pharmacist to one member, you know, it, it's not like that. It's right. Two pharmacists to maybe a hundred thousand, uh, members. Right. And. Trying to get that information in a format that can make us most effective and, and then really intervene at before. Something happens before even that prescription gets taken is a huge challenge.

And I think the tool, the study that, that we were able to publish on, on utilizing surveyor health technology, uh, really, really points towards a, a real novel use of, of the marriage between technology and all the geeky stuff and what, what we could do with the clinician who ha doesn't have a lot of time, uh, and then has to sift through a lot of information to make that person make help.

That person makes the right decisions and right recommendations to work with providers and, and patients together for the optimal outcome.

Mike Koelzer, Host: Are there some physicians or pharmacists? outside of this plan. And the first time they hear something like this is like a phone call to them at an independent pharmacy,

Ed Jai, PharmD: but you bring up a good point.

How do we, uh, where are we and what are we trying to do? And how do we interact with our members? And one of the things that, uh, you pointed out was, uh, you know, we, we are not maybe right there with the member. We're not at the side of the physician as they're writing a prescription. Uh, and so we have opportunities to identify these.

I think issues that were brought up by that Eric mentioned, and that we just talked about, uh, in various different venues. One could be of course, where, where a stratification of those members and their medication regimen sort of illicit or produce a trigger. And then that goes to a clinician, a pharmacist, for instance, in this case, uh, when you're doing a comprehensive medication review, And engaged in something called comprehensive medication management, which you, you may be aware or your listeners may be aware of is, is one of the key activities that we can offer, uh, patients, uh, members nowadays, which is looking at their medication regimens, uh, looking at their disease states, looking holistically and having a longitudinal, uh, relationship with a member.

And part of that is taking their current medication. Their disease states, their history, the unique, um, individual, uh, with regards to how they react with medications, uh, and, and their disease states, and then sifting through that information as quickly as possible. And then making the right medication regimen ahead of time.

Mike Koelzer, Host: You can do, like, what if scenarios? Right. So in other words, you're not just saying we dispense this and it's kind of written in stone. It's at the pharmacy already. Let's see if there's an interaction. You're really looking at kinda what if stuff, right. You're running across stuff and saying, what might be the best drug for this person looking at all?

Ed Jai, PharmD: Oh, yeah, that's the cool, sexy part of, of this technology that surveyor health developed is you can see visually actually kind of a, uh, a overview of say a member and their medication regimens, a side effects that are additive, and, and then the recommendations kind of distilled in a way that allows you to go and say, oh, this, this is the priority.

I better go. And. Do this first, then I can do this second, do this third address, maybe the side effect as was mentioned earlier, maybe there's additive side effects for [00:15:00] constipation or additive side effects for something even more serious, right? Arrhythmia, uh, QT interval prolongation with some cardiovascular, uh, uh, agents or agents that affect the cardiovascular electrical system.

I mean, those things are serious to anybody and I would not want to experience that or additive side effects that it's hard to look at, say 10 different drugs right away, and then distill all the additive possibilities of those side effects. And then bring about a recommendation with that, this cool technology, like I said, can really distill

Erick von Schweber: that.

I just thought I would add a quantitative example too. Because sometimes the numbers help us appreciate the qualitative changes. So, uh, in this particular high risk cohort, the average number of meds they were on was around 25, 26, what we saw in many cases. Okay. So let's say you've got six meds that have a risk of Brady, cardio of slow heartbeat, which can cause fainting and falling.

And of course in the elderly that's verboten, uh, let's say that the risks of causing bradycardia vary from less than 1% to no more than 10% for these six of 26 meds. And we've seen this very often. Okay. When you do a full holistic combinatorial analysis, their risk of bradycardia is now 25%, one in four.

And so if this is a patient who especially has had, uh, rep has presented with falls or dizziness or fainting, you would like to adjust those, whether you're adjusting the formulations or the doses or deprescribing or whatever, but the numbers get scary very quickly.

Mike Koelzer, Host: I'm just thinking business wise, not every one of your members is fed by an internal pharmacist of the plan.

They're able to use their insurance at a pharmacy in town, right? Yeah.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yeah. It's very important to know that. We have various different ways in which patient members can get their medication so they can use any pharmacy that's in our network, of course, physicians that are in our network. Uh, and so there's all this information out there.

The nice thing about being a plan of course, is that, uh, we have to pay the bills so we know which pharmacy a prescription was filled at. And if we had to pay for that medication, we know what medications are being filled. And presumably the patient is taken.

Mike Koelzer, Host: Who's getting all this information because in my mind at the pharmacy, it's kind of too late, you know, you're looking at one interaction, you're not laying up this beautiful information that the surveyor comes up with.

So when does it really bloom? Is it your computer? That's sending a warning to the patient that they should check with their physician. I mean, it seems like when it's done. After the fact it's like too late, is this kind of like a little bit of an instigator, the information that comes out that says, Hey, check with your doctor on this.

It seems like it almost has to be proactive in a way.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Well, we want it to be more proactive. And, uh, you know, one of the more interesting measures that we have with regards to healthcare is physician productivity. And you may have a physician that on average across the country has to see 30 or 35.

Patients a day. So you can imagine maybe they have five minutes, 10 minutes with a patient on average. And how do you take care of four or five different disease states and 20 different medications? So one of the issues is of course, just time to even review information, uh, and this product, it would be great if it was integrated actually with, uh, electronic medical records at the time of prescribing.

But that's not true right now, although I think that's one of the things that should happen. Oh, at the time of the doctor prescribing exactly whoever's prescribing, whether it's a physician, a nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or even a pharmacist in the case of comprehensive medication management.

Mike Koelzer, Host: If you're not doing this at the point of prescribing with all this good information and at the pharmacy, it may be too late. It seems everybody's so damn busy and the pharmacist is busy and the doctor's busy. So then when does all the great information that comes outta surveyor? When does it make its biggest impact?

Ed Jai, PharmD: Uh, well, in, in our case, what we did was we established CMM type services or comprehensive medication management services. That's the

Mike Koelzer, Host: time I gotcha. And

Ed Jai, PharmD: that relationship with the.

Erick Von Schweber: I just want to add this because IHP is serving 1.4 million members. It's not like they've got one program they're experimenting with, they're doing various tests.

I gotcha. The wrap [00:20:00] program that we did with them was specifically about saying, uh, we're getting the highest risk members who are falling through the cracks. So we need to do some advanced statistical Beigian stratification of their membership, feed that to clinical pharmacists, who could be either at the plan or could be in the community.

In this case, they were, uh, from a pharmacy at a clinical pharmacy call center who were hired under RFP by the plan. They actually received the results of the stratification. They did the interventions, they communicated with the prescribers, with the patients, et cetera. Uh, what I wanted to mention though is in the, uh, in the aspect of full transparency, IHP has other.

plans and programs going on. So they're part of an effort called California, right? Meds collaborative for, for providing CMM services where a plan is sort of the managing partner, but a community pharmacist actually performs the interventions. Uh, so I just want, you know, there's lots of ways of mixing and matching and setting the dials here.

Mike Koelzer, Host: I can see now where yes, as the pharmacist prepares for the CMN, they can kind of get this information in. They don't have a lot of time to sit with it, but they can absorb some of it over time, maybe the night before or an hour before. But then also they have the time then during. To call or that interaction then to deal with it with enough time to make a personable impact.

I

Erick Von Schweber: guess it's typically not night before. Um, so one of the benefits that our technology brings besides better identification and mitigation of risks is improvement of productivity. Hmm. So, uh, if they're just, if a pharmacist is just using the seat of their pants and a documentation tool, it can take them an hour to an hour and a half to do this level of analysis and synthesis and production of documentation.

Um, because we visualize the risk landscape across multiple factors. They do not need to spend time beforehand. We identify them in an intervention queue or a review pool. And when they click on them, all the risks are visualized. Oh, I see. They can now take that in and act on it right then and there.

Oh, I

Mike Koelzer, Host: gotcha. Yeah, they're doing it right there. They're not trying to take it and sift it through their experience and the patient's experience. It's all right there for them to share it with the patient. Yes. Interesting. All right, so I'm gonna play devil's advocate here. We have all these interactions going on and the computer does a lot of great things, but what does that mean for the patient's health and as a business person?

What does that mean for the bottom line?

Ed Jai, PharmD: Well, for instance, decreasing those additive adverse effects or drug duplications, or drug, drug interactions, uh, using this tool, uh, and studying it and implementing our comprehensive me application management type services. Uh, we were able to show practical effects on, on members and avoid events, for instance, uh, decrease in.

Emergency department visits by these members, uh, through this program of 15% on average in hospital missions by 9%, uh, bed days by 10%, total cost of medications decreased 17% and total cost of care over 19% decrease, uh, compared to a cohort. Uh, so this, this is significant and every one of those admissions or ed visits is of course, something I wouldn't want to experience, uh, in my family or personally, or one ones that we wouldn't want anybody to experience a hospital admission avoided.

We all

Mike Koelzer, Host: know how to save money in our life. If you save it, maybe you've missed out on going out to dinner or you've taken one less vacation and so on, but to combine a savings of 15% and having a loved one, maybe not have to spend an extra day in the hospital or spend a night in the ER, you know, or something like that.

It's like, Hey, that's great. That's a win-win right, Eric. I was waiting to get warmed up before we brought this term up, but quantum logic so I looked it up on, uh, Wikipedia and it's like, I didn't even know where to start with it. I ain't no genius, but I can pick up something usually, but I didn't even know if it was physics or computing.

Philosophy. I'm not even in the right damn

Erick Von Schweber: category. It's [00:25:00] all of those. I'll put it very simply. And I will refer to this the way my mentor David Finkelstein did. Um, we have gone through and why I say we, I mean, as a society, a culture, yeah. We've gone through several revolutions in physics. Um, and each one has introduced a new kind of relativity.

So there's special and general relativity that shows the relativity of time and space and motion. Yeah. But then my mentor, David Finklestein realized that. When quantum mechanics came along, this was introducing a new relativity and a new shift in our worldview, literally at a lower level, a level lower than, than special and general relativity, which is about geometry.

This was a change in the logic that we do. So you can think of human communications and human logic. At least ostensibly it appears to be bullying. Okay. If you really look and do what psychologists do, no, it's not , but if you, we, we think we're logical agents and follow bullion logic. When you look at experimental data, that's been confirmed in, in experiments over and over and over for decades and decades.

What you find is that the logic of the subatomic world is not bullying. And, and I'm gonna give a, I'm gonna try to give you a correlation here over to healthcare and medication risks. Sure. The great physicist and, uh, nobel Laureate, Richard Fineman. Okay. He created something that's called quantum electrodynamics in order to identify what's likely.

Result of an experiment, where will a photon, where will an electron end up going? What's its most likely trajectory, what's its most likely destination. And what he ended up finding out from his genius work is he said, you have to look at every single possible path that that photon or electron or quantum can take in going through your experimental apparatus.

And you now need to do an integral across all of those paths in order to find out what's the possibility and the probability of what it's actually gonna do. And so in some sense with medications, it's something similar. You can't just look at risks in isolation. You've got to look at players in triplets four times, uh, because they all have different manifestations of risk of, of risk and of effects.

And so, uh, that's partly what inspired us is that the logic of the world is different. And you, you probably are aware just because it's, uh, in popular media these days. Um, quantum computing is actually making some serious inroads to creating, uh, far cheaper and far more, uh, copious, computational resources, able to solve problems that even the largest parallel, super computers are in the internet.

Couldn't. okay. And so, uh, that is qu using quantum logic and quantum computing to achieve a quantitative speed up. It's also possible to take revolutions in the foundations of physics and apply them to qualitative differences. So we're getting both speed up of a quantitative nature. We're not using physical quantum computers, the way that IBM and Google and others are.

Uh, but there are qualitative things that we've learned to bring out of the foundations of physics. And in this case, uh, this is what we did with it.

Mike Koelzer, Host: All right. So I'm gonna, I'm gonna throw out a few terms that come to my mind when I think of what you said right there. And I don't understand it, but let me throw some terms out.

I'll just throw 'em out and I'll just sound halfway smart for the listeners. If we don't use 'em for our conversation here. And if we do use 'em fine, but Schrödinger's cat.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yep.

Mike Koelzer, Host: That has something to do a little bit of that. Yes. The electrons that we saw in college, in high school with the cloud electrons, it doesn't look like our solar system.

Basically those electrons pop in and out wherever they want to. That's number two. And then third is the problem of the traveling salesman. As far as planning a route is really, really complicated. Even if you have like 15 or 20 stops, it becomes like factorial. Yeah, it's huge. Are those sort of in this topic or am I way off on

Erick Von Schweber: those?

So I'll handle those in reverse order. All right. Uh, the last one in terms of the traveling salesman problem, fortunately for us, the [00:30:00] kinds of problems that we're working on here are mostly combinatorics as opposed to permutations. So with permutations, where you have order dependencies, then you get into even larger combinatorial explosions than we have.

Gotcha. Now I, I, I will say there is certainly there when you get down into the weeds in healthcare, right? The order and the administration of medications can make a huge difference at the level of what we're looking at right now. First you're trying, you're doing combinatorics. So that was the third one.

Um, the first one was Schrodinger and Schrodinger's cat, but by the way, Schrodinger created this thought experiment, this gaan experiment in order to demonstrate the absurdness of quantum mechanics. Oh, he, along with Einstein did not believe at the, at the weirdest didn't like it strangeness that people like Heisenberg and bohr, um, and summer felt would embrace, would be open to.

Mike Koelzer, Host: So that was almost showing the absurdity of it.

Erick Von Schweber: Yes. Uh, but of course now we, I have to say this. So I just recently, uh, participated in an online conference for, uh, sir, Roger Penrose, the great Oxford physicist and mathematician, his 90th birthday, and his awarding of the Nobel prize or sharing of it. Uh, and so a lot of this just recently came.

We now have no cats that are in the quantum superposition of alive and dead. We don't have anything that large macroscopically, but we've got some pretty large molecules at this point. And so far, quantum mechanics is not interesting. Lots of philosophical problems to embrace.

Mike Koelzer, Host: All right. So then the third one about the electrons, not being like a solar system, because those come in and out where they want

Erick Von Schweber: to you're right.

What you have is the best information we have of those, uh, entities under study is a probability called the probability density matrix or the distribution of probabilities. And then you have to do an integral over all of those paths to figure out what's likely to. So it's not that different from what we have to do now to advance medication risk, uh, assessment and mitigation, because we also have to look at things far more holistically yeah.

Then we've been able to do it. Right.

Mike Koelzer, Host: So ed, you heard Eric and me instructing him on where he was incorrect on stuff but yeah. In your wildest dreams, what would you like to see, knowing a little bit about what this program does so far, and it's an introductory program with your guys experimenting with some other programs you're using too, in your wildest dreams.

If you could say to Eric right now, invent this. take your damn cat or whatever you have to do to invent this and invent it. What would you want?

Ed Jai, PharmD: well, you know, it, it's, uh, one of those things where I think we, we always need to go and think beyond where we are right now and some of the most important things I, that pop up in my mind when, when Eric's geeking out and you're talking about electrons and things like that future, uh, is to get to that like star Trek, transporter, right.

Where, you know, we can't even imagine how to do something like that. Move a body from one place to another and yeah. And still be alive and working. Yeah. But, you know, for healthcare, we become so much more complex. Uh, there's so many drugs now, drugs that we never used to have for a disease state. Uh, and we have newer diseases than we've had, you know, 20 years ago.

We've identified that needs, uh, therapies and, and so most therapy, most chronic disease is addressed through medications. That's a fact. And so for, for what you just asked, like what, what should we do with Eric and what, what do we need to do Eric for the future is, you know, we, we need to take what you've developed this artificial intelligence and continue to refine how to, to develop that, that computer human interface.

I think that would be kind of cool. If I had this little thing I could go and attach to my head it would really go in and help me make decisions, help the clinician make decisions with regards to optimal medication management or optimal medication regimens, um, in, in order to, to improve outcomes, results and decrease, uh, the problems, the, the medication events.

I mean, we, we just don't, I think have enough brain power, an individual like you and me to sift that much information when yeah. Uh, we have dozens and dozens of drugs being [00:35:00] approved. Uh, every year more than that, actually. And how, how do we keep up with knowledge? Uh, we have a huge amount of knowledge, uh, um, you know, doubling and how many, how many, I don't know.

Do you guys know that statistic at all? Like how often that knowledge

doubles?

Erick Von Schweber: I think it used to be 18 months.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yeah. So how do we actually deal with that as humans? It's impossible without these kinds of technologies. And I would say transformational knowledge management tools or decision support tools.

Mike Koelzer, Host: It got me thinking about how at the amusement parks, and by the way, I can tell I'm an old guy now, because I used to go to amusement parks. And I said, the day that I stopped riding on roller coasters is the day that I'm an old fart. Well, I didn't say fart back then, but I said that's when I'm an old guy, when I stopped riding on roller coasters.

And that was about 20 years ago. I just can't take it anymore. but my point is roller coasters. . On YouTube, they've got one it's called like the suicide coaster. In other words, you can build any kind of roller coaster you want to, you can make a coaster that does like 10 loops and it kills you because your blood just stays in your feet and you're all dead at the end of the ride.

But I think we have that problem with medicine, you know, is that you can make these better medicines, but unless, you know, the right people to give it to and the interactions it might cause, and who's the right candidate for this and this and this, it's like a huge, well, I know it's not the serial of the traveling salesman, but it's a lot of moving parts for that.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Oh yeah. Just an incredible amount of digestion of information. It would require. For us to even be adequate at designing, you know, the right interventions in a complex patient that has 60 meds , which is not that uncommon. So

Mike Koelzer, Host: How do you think COVID has benefited the medical profession as far as computer use, telemedicine, those kinds of things?

It seems to me that it sped things up by about 10 years. What are you guys seeing as far as anything in your area?

Ed Jai, PharmD: Oh yeah. Well, that has been a topic at the front of our minds here at I E H P we, we recently were proposing a remote patient monitoring technology. For telehealth expansion in our, our members and with partnership with our providers.

And, you know, it was very interesting pre COVID when we started talking about it. But as soon as COVID hit, there was a scramble and people were trying to figure out how do I see patients when they don't even want to come to the hospital? They don't want to come to a point. We don't even want them coming into a clinic or to a medical officer, because we just don't have the ability to, to, uh, to prevent COVID infections in these close, uh, settings indoors, uh, adequately the way that we have things physically laid.

And so that has resulted in a huge level of interest in our partners when we started proposing this remote patient monitoring project and, and truly the CMM that, that we have been, uh, experimenting with with survey health was mostly, uh, really te telehealth and, and encounters not face to face. And so we see a dramatic increase in telehealth visits during COVID, uh, that continues on to, um, also with CMS approving during COVID, uh, these, uh, I guess flexibility, they called them with regards to the payment of visits so that we could do that over the telephone, even, uh, asynchronous.

And those, a lot of those have become permanent now and expanded telehealth flexibilities, and including with the state of California where we're located, uh, the governor proposed, uh, and this year it's supposed to be implemented, uh, payment for remote patient monitoring services in the Medicaid population, which is a huge.

Huge change. And so we see, uh, to your point that there's been a huge interest, a large, uh, effort, uh, on many health systems providers to expand telehealth services. And, when we did some outreach on champion sites for our remote patient monitoring technology implementation, uh, these larger health systems that we were dealing with, uh, were saying, yeah, this is part of our strategic plan now.

And before it used to be maybe less than the majority of health systems wanting to implement, uh, this kind of telehealth patient technology as part of [00:40:00] a, you know, top priority. Now it's become the majority of providers seeing this as a top priority. I'll just

Mike Koelzer, Host: make a decision that things seem to go well with this program.

Ed tells everybody to hire Eric and and multiply this by like a hundred what's stopping that. Are there any bottlenecks to what happened in this study to then

Ed Jai, PharmD: expand? Well, I would say the main bottleneck, of course, I'm, I'm a huge fan of, of surveyor health and Eric and Linda and what they've been able to accomplish with us.

But a huge bottleneck is just trying to balance from a health plan perspective. What are the things you wanna invest in first and the return on investment second and third. And so it is one of those things where you, your voice crying out in the wilderness and you need to go and continue with the call.

Uh, one of the things that's a great result that I think is compelling is that there was a over 12 to one return on investment with regards to the costs of implementing the program as we did in this, uh, situation. So 12 to one, that's a huge return on investment.

Mike Koelzer, Host: That's huge. So while it was like 20%, let's say savings.

That's looking at savings overall, but as far as the investment, it was 12 to one.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yes. For every dollar we spent on implementing the costs of the programs overall, we saved $12 to that. Every $1 investment.

Erick Von Schweber: Right. And by cost, that includes the pharmacist

Mike Koelzer, Host: cost, not just paying the services of your company, but the pharmacist costs involved with that.

Erick Von Schweber: Correct? Correct. You asked that lovely question of ed. And one of the things that occurred to me is just before we had changed our focus into healthcare because of this health crisis with Linda's mom, uh, our last program, our DARPA program was one called sapien situation where protocols in edge network technologies.

And we never intended to say, oh, let's take sapien as a model for what healthcare could be. But here we are year after year. Now that you have real time, remote patient monitoring, you know, back in the, uh, mercury days, right? NASA mercury days, we call it telemetry. And it's much better now. Okay. That introduces a real time aspect.

That's potentially connecting the patients members plans and actors in the healthcare system in a much more real time fashion. And so I see healthcare moving to the place where we're going to be able to do it more like a battle theater, a military network that is closely correlated that is adaptive in the face of onslaughts and challenges.

And it's coordinating the members and it's optimizing it itself. So I, I, I am so encouraged by remote patient monitoring and that COVID gave it a shot in the arm because I think this is going to put us on this trajectory that really will continue to improve health and reduce cost.

Mike Koelzer, Host: When you say monitoring.

Are you talking, monitoring like electricity, like putting in your diabetes scores or blood pressure machines and attaching those? What do you mean by monitoring?

Ed Jai, PharmD: Well, when you talk about comprehensive medication management, of course, uh, you know, monitoring, uh, can refer particularly to diabetes, disease state, like, like you mentioned, it could be blood pressure.

People take

Mike Koelzer, Host: their own blood pressure, you mean, and punch it in, or they're using an iPhone or something like that. Are we talking that

Ed Jai, PharmD: that can happen with comprehensive medication management and that would decrease what we call the, the time in between interventions, for instance, if so, if someone didn't take a blood pressure, every whatever it is, week during the time that you're trying to adjust therapy or figure out if, if something is happening based upon a medication

Mike Koelzer, Host: regimen and we're talking self monitoring, right.

They're wrapping this around their own arm or something.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yeah, patient initiated or patient provided data that could come across using technology that we have nowadays. And, and that's part of the remote patient monitoring I was referring to is, if you need to, not only of course look at additive side effects of medication, but are, are those things that maybe, uh, something that you could only detect from say a blood pressure monitor, right.

Uh, blood pressure, that's going too low. For instance, could be a side effect or an extension. If you don't have data like a blood pressure coming across weekly or even daily, sometimes when you're adjusting therapy, then you won't know, oh, is the patient experiencing the, [00:45:00] the effect of that medication that I wanted?

Or is it too much of an effect? Uh, and. That could be a weight scale that could measure, for instance, in the heart failure patient, whether a medication regimen is working to decrease the water weight that comes when your heart's not pumping strong enough. And of course your, the, the water is going into the lungs, the water is staying in your body and, and not, uh, leaving.

So these remote patient monitoring or patient provided data that can come through the technology and then come in front of say, if pharmacists doing comprehensive medication management is really important. Cuz without data, we, we have nothing to react to

Mike Koelzer, Host: or going Erik through your stuff, unbeknownst even to the pharmacist, right.

It's just plugged right into it. Some.

Erick Von Schweber: So I'll, I'll, I'll put something in there. So along with this study on the wrap program that was published by JM C P we also have another study that we've done with IHP so far, we've not submitted for publication yet, which is a full randomized control trial on applying the platform for not just doing CMM, but for diabetic patients where you're also doing diabetes disease management.

Now that program required those clinical pharmacists to speak to the patient and get their self monitored blood glucose levels, as opposed to, uh, Having it done automatically under the covers. What we saw there is even with all the intense manual effort of collecting this data, the payoff was a 30% increase in the likelihood of these members getting under A1C control.

Wow. So HBA ONEC less than eight. Now. Imagine now, once we have that telemetry in place, we can do it. Without requiring so much manual intervention, right? That means you can provide it to a larger swath or larger cohort of members. And so you're helping deliver what was the, uh, the triple a and one of those was availability and access.

So yes, we want to reduce costs. We want to improve quality and we want to improve access. And so to me, this issue of bringing telemetry or I should call it remote patient monitoring as it is dubbed these days has enormous, uh, potential.

Mike Koelzer, Host: And certainly I imagine the mobile phone is a huge part of that and apps and little attachments that go along with it.

Ed Jai, PharmD: You certainly, uh, bring your own device B Y O D . Uh, we could use smart phones and apps that have this kind of ability to, for instance, Bluetooth with a blood pressure, cuff weight, scale, heart monitors, pulse OSX to measure oxygen in the blood. All those are available right now, uh, to connect, uh, the member with, uh, a, the, a data stream to the provider and to other healthcare team members,

Mike Koelzer, Host: voice technology.

I think you can learn a lot from voice. So Alexa, you know, Google says, hold good morning, Mrs. Smith. You know, how are you feeling today compared to yesterday? That's question number one, you know, where is your pain? Is it above your waist or below? In other words, with 20 questions with, you know, health or voice, I think you could learn a lot.

Have you seen anything with the voice in monitoring? Oh

Ed Jai, PharmD: yeah, definitely. I mean, the there's so much new development of, uh, this technology in all areas, whether it's, um, streaming video from members or patients, uh, into this, uh, te telehealth technology, uh, could be live or could be recorded after hours and then sent asynchronously to doctors.

Uh, we've. Seeing where technology, for instance, can prompt, um, members or patients, uh, with regards to symptoms. Are you feeling shortness of breath? Uh, have you taken your medication today? And if so, can you just let us know by pressing this on your smartphone or, or just, uh, telling us right now and, and, uh, we'll, we'll go and process that information.

And a lot of it's by bots too, and artificial intelligence that can really sift and, and also filter out the noise, uh, and then establish what is really, uh, important. And then actually get that to a live person.

Mike Koelzer, Host: Two grand rapids have to pay your water bills. So in other words, it's like, what do you want to do today?

And you say water B. So a boy like that, that narrows it down, basically.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yeah. Yeah. And depending on the patient's answer to the question like, oh yeah, I am feeling kind of tight and short of breath right now that could immediately set off another set of questions. And then depending on those answers, [00:50:00] then that can escalate yeah.

Immediately to, to a process that would allow the rapid intervention to prevent that person from going to the end. Yeah. Right. Uh, or having, uh, an admission. So this is exciting.

Mike Koelzer, Host: I was on the I E H P website and I thought it was cool. Some of the very cool graphics about some of your programs, you have smoking and weight management and things like that.

I was just talking to my brother-in-law yesterday and I was saying. how many chronic conditions could be solved by finding a way to get people, to walk, you know, three miles and to not have a donut, have ag or oatmeal instead of a donut, and then pick your third thing, you know, not light up for a cigarette after that, something like that.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yeah. If we could have like, uh, an angel on our shoulder, ,

Mike Koelzer, Host: That's what I'm asking Eric, come up with something for that. Yeah. There's really nothing to save someone from their vices. Really. You can incentivize it. You can do a lot of things, but there's probably not a way to do

Erick Von Schweber: that. I'll throw something out there and we are not working on this, but I will tell you my own sort of title election.

So Linda and I have been vegan for over 30 years, healthy vegan, as opposed to, you know, eating CRO and . Well, I croon is butter, not a Popsicle vegan. There we go. Yes. Uh, One of the things we've found is, uh, what I would call reprogramming abilities of the human biocomputer. I think that's what John Lilly MD wants to refer to.

As what we've found is if you allow yourself, if you do dietary changes and you have someone who's hopefully helping you through those, if you can keep them persisted long enough, you will have both your biome in the gut, as well as your, your, your neural networks. We will reprogram, and you can actually change what you like.

And so I have great hopes. In fact, I've had conversations with the director of program evaluation at I H P, a lovely fellow named Will, uh, about how we can get a handle on people's diet and lifestyle and nudge them in a more useful direction. How do we even understand what they're taking in so that we can address them in, in the right place as opposed to a place that they won't be responsive to?

Um, I actually think there's lots of hope there. Uh, uh, I think I've read about some plans that are literally sending out meal kits to people. So it's like if you, if you make it easier for them to do something healthy than to do what they normally do, easier and cheaper, well, people will often do. Yeah,

Mike Koelzer, Host: I know that there's so much research right now, and God forbid I get into anything real medical on this, because this is a business podcast.

And as soon as I start talking about medicine, I screw stuff up, but there's a lot of gut bio and all that stuff where it's like, well, what comes first? You know, depression in the head or the wrong. Serotonin receptors in the stomach that are causing this and all that kind of stuff. It's a huge, huge new area.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yeah. I think you, you brought up something really interesting, Mike. Yeah. If we had a little voice that really altered that decision before we took the donut or the bad vegan decision, I don't know. we would probably solve a lot of problems. Definitely. Disease states are a lagging indicator of maybe our overall health and weight problem we have in the United States.

About 10 years

Mike Koelzer, Host: ago, I started getting migraine headaches and I get 'em from nitrates in some of the processed meats. I don't know if it does something to my blood vessels in my head. So I get these terrible migraines about eight hours after I eat, you know, bacon or processed meats. And it takes zero willpower for me to say, no, I'm not gonna have bacon, or I'm not gonna have, you know, that hot dog because.

I know I'll get a terrible headache and it's zero willpower. And I can make that decision so easily, but have me make that decision for a donut or bacon, if it had to do with my weight or heart disease or whatever, I have no willpower for that. Maybe because the headache lasted eight hours, but it was heart disease.

And, and that is. 30 years when I dropped dead. Maybe it has to do with the length of time between the source and the penalty. I don't know.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yeah. Yeah. So we should have a voice with a cattle prod immediately built in. That's what Eric could develop. Eric,

Mike Koelzer, Host: You have to invent a dog buzzer around the neck or something like that.

Your apple

Erick Von Schweber: watch could start shocking you, right? exactly.

Mike Koelzer, Host: There you go.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Sometimes simple solutions are the

Mike Koelzer, Host: best solutions. Here's a lesson for you guys. You didn't [00:55:00] know you were gonna learn from me right on the spot. When you take the shock collar off of your dog, because you're gonna go somewhere with your dog in the car.

And the shock collar starts buzzing. Meaning that it's shocking. Don't grab it from the center.

that's a free

Erick Von Schweber: one for,

Ed Jai, PharmD: yeah. That's wisdom from experience.

Mike Koelzer, Host: I was watching on YouTube last night. And they were showing. And Eric, this is to your point about a gut biome, you know, even talking about that, but I was watching this YouTube and they were showing biology, 3d animation, you know, showing how cells actually work.

And they're showing the, the, I don't know all the cell parts, you know, but they're like little robots, you know, they're actually marching down the path and when the DNA splits it, you know, one side of the DNA, whatever the hell that's called goes through fine. But then the other part in the cell, it cuts 'em into sections, flips.

'em puts 'em on the other side and then brings 'em back together. But the guy's point was basically, those are machines, they're small machines, but they are machines. And there'll be a day when humans think we can make stuff small. Now wait for a hundred years when we start making little cells.

Electronic cells that we put into people to replace the cells that are there doing these mechanical tasks, actually inside the cell.

Ed Jai, PharmD: oh, that would be cool. I think we're still trying to figure out the mitochondria. How did that come into existence? It's

Mike Koelzer, Host: amazing. so, Eric, if you could pick a different industry right now, let's say that healthcare says we don't need Mike.

We don't need Eric. We don't need ed.

Erick Von Schweber: Go do something else from the Twilight zone, those, uh, extraterrestrials who want to come to serve, man, they come, they give us a pill. They cure all diseases. What other industries

Mike Koelzer, Host: would you go besides military and health, if you had to

Erick Von Schweber: before COVID when making travel arrangements was consuming way too much of my time, I have always wanted to do an application in travel.

Where we literally would look at all possibilities, all flight combinations, all taxis, all Ubers, all hotels, everything you could do, and then figure out what are the trade offs, because that's one of the things that we didn't talk about here because healthcare rarely has solutions that are ideal in all respects, everything has good points and bad points.

And when you start combining therapies where you have 10 or 25 or more meds, you now have multiple trade offs working against each other, and you have no idea what is going on. Being able to do that for travel arrangements and then figure out which make the optimal trade offs. That would be lovely.

Another one we've contemplated is financial portfolio analysis. So now you're really talking about, which are the likely scenarios that will gain you the best with the lowest risk, that kind of thing. So those are some of the things we've thought

Mike Koelzer, Host: about. I knew my traveling salesman comment would hit home but that's harder than because it's serial versus just kind of throwing 'em into a bucket.

Erick Von Schweber: Well, I don't think we would create someone's in that venue. We would create someone's itinerary of saying you're gonna go Boise first and then you're gonna go to salt lake city. I think we would let them create their IN their itinerary and then figure out how to, uh, optimize their trade offs around it.

Oh, I

Mike Koelzer, Host: see. So they would've already set up basically the points a through Z. And now you're saying how to finesse that to make it better.

Ed Jai, PharmD: Yes. Hey, and if you could take into account my, uh, 86 year old mom in that miss as a variable, that would be even better. So I'd buy that. .

Mike Koelzer, Host: I think our average listener is like 40 or something like that.

If you look at the curve, that's kind of the, the general listener, even though pharmacies is like 70% female, I think our listeners on average, their men, like 70% men, should that group care or are we just looking at old farts that we're talking about being on all these medicines? Can we take a break and just think about this 25 or 30 years from now?

Erick Von Schweber: No, uh, the, the answer is if you are a patient on a polypharmacy drug regimen, it really doesn't matter how old you are. You are going to have risks. And many of the risks are typically unknown. Uh, they have not been computed. They've not been computationally predicted. Uh, so for example, our study was largely of people, 40 to 64 years old, a few, a few people aged into the.

Realm during the study, cuz it was sufficiently long. But what we found in analyzing both that data, as [01:00:00] as well as the data, on Medicare populations, people 65 and older, because I just wanna acknowledge IHP is the largest, uh, public Medicare Medi you know, dual plant in the country. So we had, uh, lots of copious, robust data to analyze on the seniors in Medicare versus these Medicaid members who were middle aged.

And we found the risks of the middle aged Medicaid members are almost as high as the seniors. And to me, that was a huge surprise because it's typically believed, take things like Medicare part D medication therapy management and get it out to those people who are in the Medicare realm. Uh, so now we find there's a much larger constituency who is at

Mike Koelzer, Host: risk.

Anybody who's talking. All those medicines. Yes. It's problematic. Yeah, it can be, can be, it can be, can be, can be. Yeah. Hmm. Maybe some of the moral of the story is put my tennis shoes on, put my donut down, don't smoke my cigarette. I don't even smoke cigarettes, but I'm not gonna start but maybe the moral of the story is try to maybe stay off some of those drugs in the first place.

But if you have to realize that that polypharmacy can be causing a lot more problems than you realize,

Erick Von Schweber: and it needs to be managed and providers don't have the time to do that

Mike Koelzer, Host: are some of these interactions so crazy that you might not see any of 'em until five different medicines come together and cause some kind of a soup in the gut would a pharmacist with enough time come across all these or are there some that are so out there that only the combination of five or.

Eight or 10 of these different chemicals are gonna bring something up

Erick Von Schweber: the, the short answer. See if I can give you a short answer, um, especially where you're going into combinatorial effects. So when you look at the drug interaction landscape, the evidence that has been collected, which is typically on smaller scale academic cohort studies for interactions, as opposed to your primary added, uh, your primary side effects that are found in your, uh, FDA approved clinical drug trials.

Yes. Um, in these smaller academic studies, they may be identifying specific interactions. Typically it is bimodal. Sometimes it'll be tri modal, but people have not been looking at what is the consequence. Three or four or five or six meds together. So because pharmacists, uh, are trained in a certain fashion and they're accustomed to certain things, we will still divide what we call the risk landscape across the, uh, additive and combinatorial effects specifically separate from the specific chemical interactions.

Um, so they can look at both, but certainly amongst the, uh, combinatorial effects, most of them are pretty novel. And, and I would say your well trained experience, pharmacists may know some of them because of their experience and the brain's capacity to see patterns. But to get this deployed consistently across at scale, across many, many pharmacists, providing this kind of intervention for a huge number of, uh, members in a cohort, uh, that there has been no consistent way to do that.

I fit two of

Mike Koelzer, Host: those. I am well trained and experienced, but I've had so much time to experience stuff now that I've forgotten all my training so I definitely need your program.

Erick Von Schweber: we typically do not look at the regulatory silos. Um, you know, you've got part D MTM and CMM. You've got transitions of care and med rec.

You have comprehensive care management that providers are ostensibly supposed to provide for aging populations. All of these are very similar. Modus opera, a similar purpose. Uh, and I think we could do a much better job than stove piping them. Let's do it based on the healthcare data that we are collecting faster and more rapidly through example, remote patient monitoring, and let's figure out who's risky rather than do it in the, uh, the glacial pace of a Senator Congress, introducing regulations and legislation.

Uh, so I think there's a much greater community to be served and I think they can be served more effectively once we get past all the regulatory stove bites. Of course, that's probably asking for something, uh, more than a transporter device. yeah.

Mike Koelzer, Host: Would it be fair to say let's use the computer programs and what we've learned here to then.

Find out who needs [01:05:00] more of this, is that right? Yes. Yes. Don't wait for these old studies of we're gonna do a, B, C let's find out who needs it and let's get it going

Erick Von Schweber: and we can do it affordably at scale. That's the thing that, to me, there's multiple results of the study. The main one is this kind of effective intervention.

This can be done at scale and affordably, as opposed to where are we going to get the money to hire all the pharmacists? We need to get this to serve our members

Mike Koelzer, Host: almost every. Industry has taken technology and made stuff cheaper. Medicine and pharmacy are about the only ones that have gone in the wrong direction.

They've used the technology and everything's so much more damn expensive. So comments like that. Yeah, it can be done. It will be done by just getting rid of some of the red tape. It seems we're all doing it. Yeah. Yeah. We're doing it. No, you guys are doing it. I'm just sitting here on my fat ass talking to you about it.

All right, guys. Really a pleasure. We'll be following. So keep up the great work. Thank you so much. Thanks Mike. Thank you guys. Talk to you.